Description

Did you know that roughly 85% of ALL the nutrients our body requires have been farmed out of the soil our food is grown in… even organic? Most people are literally living on 15% fuel! Can you imagine how you will feel when you replace the 85% of nutrients missing and your cells are operating at 100%? It's a game-changer! In just seconds a day, this ultra-concentrated Plant-Based powerhouse makes Transforming your health simple and convenient!

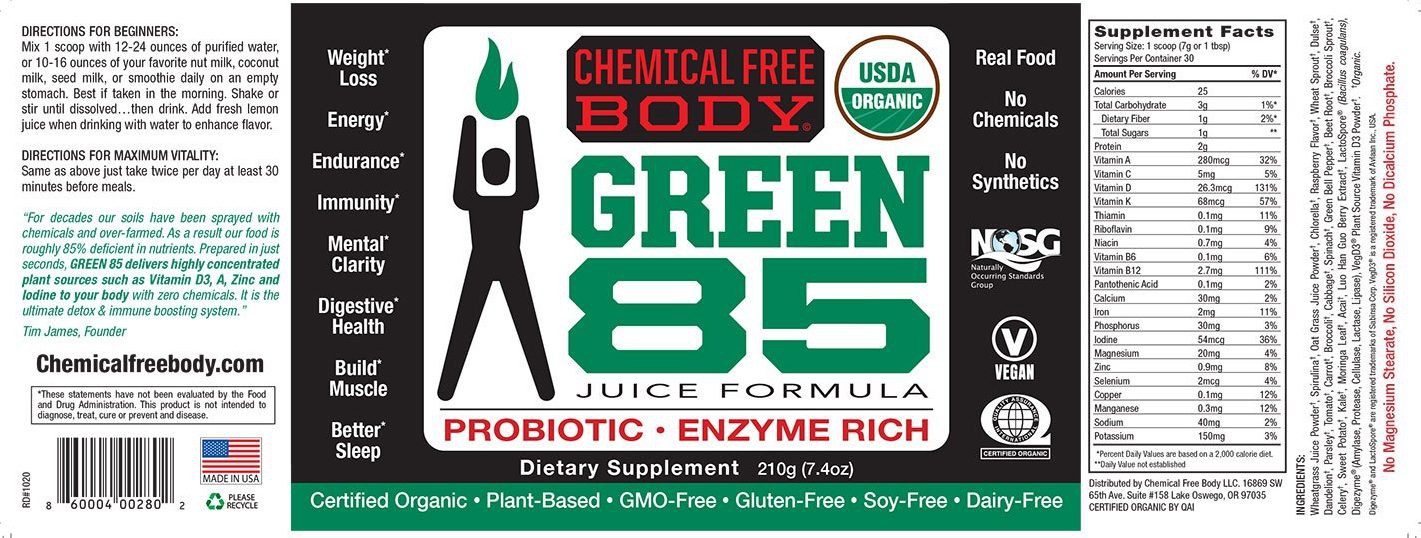

DIRECTIONS:

- Take it first thing in the morning on an empty stomach and again in the late afternoon at least 30 minutes before dinner.

- Mix one level scoop in 12-24 ounces of purified water by stirring with a spoon or shaking in a mason jar.

- You can also add it to a smoothie or shake.

- For a complete “Meal Replacement” mix with 10-16 ounces of nut or seed milk.

- To enhance flavor or help with taste issues add lemon or lime juice or mix with unsweetened cranberry juice.

Science

GREEN 85 JUICE FORMULA (The Science)

Replacing critical nutrients farmed out of our soil

#1 & #3 Concentrated Grass Juices Blend

(Wheat & Oat) Grasses, the first land-based organisms, possess a complete matrix of proteins (in amino-acid form) to build a strong muscular body. They are also rich in Chlorophyll which is very similar to the structure of our own blood. Grasses can neutralize toxins and detoxify us while rejuvenating us on a cellular level. [1-13]

#2 Spirulina

Amazing source of predigested and complete proteins that regulates blood sugar. Spirulina is also high in iron and calcium. It’s great for women during PMS or anyone with inflammation due to its gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), a powerful anti-inflammatory agent. [13-23]

#4 Chlorella

Chlorella is a green algae and is one of the highest sources of predigested and complete proteins. Rich in Vitamins B, C, and E with an array of peptides and polysaccharides. Reduces food cravings and helps to remove heavy metals from the body like mercury.[25-34]

#5 Raspberry Extract (flavor)

Cold Pressed raspberry extract is loaded with antioxidants to protect us from free-radical damage and absolutely delicious! [35-40]

#6 Wheat Sprout

Wheat sprouts are a rare source of a special compound known as Super Oxide Dismutase (SOD), which helps the body to repair itself quickly, slow down the aging process, and reduce inflammation. It's also high in folic acid which is great for heart health, brain function, antidepressant activity, and a great detoxifier! [40-42]

#7 Dulse

Dulse may be best known for its high iodine content to improve thyroid function but has also been clinically proven to possess free radical scavenging activity, making dulse a useful antioxidant. Seaweed has also been demonstrated to inhibit the growth of fat cells in the laboratory. Utilizing dulse may help to repair compromised body tissues. [43-44]

#8 Dandelion

It is one of the top 6 herbs in the Chinese herbal medicinal tradition and is rich in fiber, potassium, iron, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus and B vitamins, thiamine, and riboflavin, and is a good source of protein. Assists in weight reduction, cleansing the skin, and eliminating acne. Purifies blood, cleanses our system, and otherwise improves gastrointestinal health. Prevents or lowers high blood pressure, lowers cholesterol, and balances blood sugars. [45-46]

#9 Parsley, #10 Tomato, #11 Carrot, #12 Broccoli, #13 Cabbage, #14 Spinach, #15 Green Bell Pepper, #16 Beet Root, #18 Celery, #19 Sweet Potato, #20 Kale

A blend of concentrated juices which contain phytonutrients that bulletproof your immune system. A great way to get your servings of veggies that is quick and convenient. [47]

#17 Broccoli Sprout

In 1992 researchers at Johns Hopkins doubled broccoli sales overnight when they discovered a phytonutrient called sulforaphane greatly increased the body’s ability to ward off cancer.[48-55]

#21 Moringa

Nicknamed worldwide as “The Miracle Tree”, the leaves are nature’s Multi-Vitamin. This is a food plant with powerful antioxidants and multiple health uses along with the ability to suppress appetite and promote weight loss. [56-67]

#22 Acai Berry

Pronounced as “ah-sigh-ee”, acai is a reddish-purple berry that grows on the acai palm tree mostly found in Central and South America. The Acai Berry has been consumed by humans for thousands of years. Regular consumption prevents oxidative damage in our body, thus protecting us on a cellular level and keeping us looking young! [68-70]

#23 Monk Fruit:

Monk fruit is an awesome sweetener! It is 170 times sweeter than sugar with no downside. It helps to regulate blood sugar, which is great for diabetics or pre-diabetics. Also helps reduce food cravings and has no weird aftertaste. Yum! [71-79]

#24 Soil-Based Probiotics (Bacillus coagulans):

Probiotics are the good bacteria in our gut that comprises what should be about three pounds of our immune system. Probiotics help to establish that good bacteria so we can have ideal bowel movements, improved cognitive function, and a stronger constitution. A must in our toxic and highly stressed world! [80-82]

#25 Digestive Enzymes

Digestive Enzymes assist the breakdown of food molecules while improving digestion and bowel movements. Neutralizes indigestion with no side bad effects. Digestive Enzymes also carry electric frequency to our cells that literally charges up our battery (our cells) with energy while fighting off free-radical damage keeping us looking young and feeling great. [83-91]

#26 Vitamin D3

Green 85 contains naturally occurring, non-synthetic Vitamin D3 (Cholecalciferol). Most Americans are over 40% deficient in Vitamin and most people in the world are also deficient. Vitamin D is important for regulating the absorption of calcium and phosphorus, and for facilitating normal immune system function. Getting a sufficient amount of vitamin D is important for the normal growth and development of bones and teeth, as well as improved resistance against certain diseases. [92-96]

References:

- Hughes and Letner. “Chlorophyll and Hemoglobin Regeneration,” American Journal of Medical Science, 188, 206 (1936)

- Patek. “Chlorophyll and Regeneration of Blood,” Archives of Internal Medicine. 57, 76 (1936)

- Kohler, Elvahjem and Hart. “Growth Stimulating Properties of Grass Juice,” Science. 83, 445 (1936)

- Kohler, Elvahjem and Hart. “The Relation of the Grass Juice Factor to Guinea Pig Nutrition.”Journal of Nutrition, 15, 445 (1938)

- Rhoads. “The Relation of Vitamin K to the Hemorrhagic Tendency in Obstructive Jaundice (Dehydrated Cereal Grass as the Source of Vitamin K). Journal of Medicine, 112, 2259, (1939)

- Waddall. “Effect of Vitamin K on the Clotting Time of the Prothrombin and the Blood (Dehydrated Cereal Grass as the Source of Vitamin K).” Journal of Medicine. 112, 2259 (1939)

- Illingworth. “Hemorrhage in Jaundice (Use of Dehydrated Cereal Grass).” Lancet. 236. 1031 (1939)

- Kohler, Randle and Wagner. “The Grass Juice Factor.” Journal of Biological Chemistry. 128, 1w (1939)

- Friedman and Friedman. “Gonadotropic Extracts from Green Leaves.” American Journal of Physiology. 125, 486, (1939)

- Randle, Sober and Kohler. “The Distribution of the Grass Juice Factor in Plant and Animal Materials.” The Journal of Nutrition.20, 459 (1940)

- Gomez, Hartman and Dryden. “Influence of Oat Juice Extract Upon the Age of Sexual Maturity in Rats. The Journal of Dairy Science. 24, 507 (1941)

- Miller. “Chlorophyll for Healing.” Science News Letter. March 15, 17l (1941).

- Spirulina in Jiangxi China. by Miao Jian Ren. 1987. Academy of Agricultural Science. Presented at Soc. Appl. Algology, Lille France Sep. 1987.

- The study on the curative effect of zinc containing spirulina for zinc deficient children. by Wen Yonghuang, et al. 1994. Capital Medical College, Beijing. Presented at 5th Int’l Phycological Congress, Qingdao, June 1994.

- Clinical and biochemical evaluations of spirulina with regard to its application in the treatment of obesity. by E.W. Becker, et al. 1986. Inst. Chem. Pfanz. Pub. in Nutrition Reports Int’l, Vol. 33, No. 4, pg 565. Germany.

- Evaluation of chemoprevention of oral cancer with spirulina. by Babu, M. et al. 1995. Pub. in Nutrition and Cancer, Vol. 24, No. 2, 197-202.

- Bioavailability of spirulina carotenes in preschool children. by V. Annapurna, et al. 1991. National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, India. J. Clin. Biochem Nutrition. 10 145-151. India.

- Large scale nutritional supplementation with spirulina alga. by C.V. Seshadri. 1993. All India Coordinated Project on Spirulina. Shri Amm Murugappa Chettiar Research Center (MCRC).

- Clinical experiences of administration of spirulina to patients with hypochromic anemia. by T. Takeuchi, et al. 1978. Tokyo Medical and Dental Univ. Japan.

- Cholesterol lowering effect of spirulina. by N. Nayaka, et al. 1988. Tokai Univ. Pub. in Nutrition Reports Int’l, . 37, No. 6, 1329-1337.

- Clinical experimentation with spirulina. by R. Ramos Galvan. 1973. National Institute of Nutrition, Mexico City, Mexico (in Spanish).

- Observations on the utilization of spirulina as an adjuvant nutritive factor in treating some diseases accompanied by a nutritional deficiency. by V. Fica, et al. 1984. Clinica II Medicala, Spitalului Clinic, București. Med. Interna 36 (3).

- Spirulina- natural sorbent of radionuclides. by L.P. Loseva and I.V. Dardynskaya. Sep 1993. Research Institute of Radiation Medicine, Minsk, Belarus. 6th Int’l Congress of Applied Algology, Czech Republic. Belarus.

- Tamaki H, et al. Inhibitory effects of herbal extracts on breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) and structure-inhibitory potency relationship of isoflavonoids.Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. (2010)

- Rai UN1, et al. Chromate tolerance and accumulation in Chlorella vulgaris L.: role of antioxidant enzymes and biochemical changes in detoxification of metals.Bioresour Technol. (2013)

- Algal Biomass: An Economical Method for Removal of Chromium from Tannery Effluent.

- Jiang Y1, et al. Effects of arsenate (AS5+) on growth and production of glutathione (GSH) and phytochelatins (PCS) in Chlorella vulgaris. Int J Phytoremediation. (2011)

- Karadjova IB1, Slaveykova VI, Tsalev DL. The bio uptake and toxicity of arsenic species on the green microalga Chlorella salina in seawater. Aquat Toxicol. (2008)

- Wu Y1, Wang WX. Accumulation, subcellular distribution and toxicity of inorganic mercury and methylmercury in marine phytoplankton. Environ Pollut. (2011)

- Uchikawa T, et al. Enhanced elimination of tissue methylmercury in Parachlorella beijerinckii-fed mice. J Toxicol Sci. (2011)

- Uchikawa T, et al. The influence of Parachlorella beijerinckii CK-5 on the absorption and excretion of methylmercury (MeHg) in mice. J Toxicol Sci. (2010)

- The Prevalence of Anemia in Women.

- Kusumi E, et al. Prevalence of anemia among healthy women in 2 metropolitan areas of Japan. Int J Hematol. (2006)

- Borquez RM, Canales ER and Redon JP. Osmotic dehydration of raspberries with vacuum pretreatment followed by microwave-vacuum drying. Journal of Food Engineering, Volume 99, Issue 2, July 2010, Pages 121-127.

- Bowen-Forbes CS, Zhang Y and Nair MG. Anthocyanin content, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties of blackberry and raspberry fruits. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, Volume 23, Issue 6, September 2010, Pages 554-560.

- Cekic C and Ozgen M. Comparison of antioxidant capacity and phytochemical properties of wild and cultivated red raspberries (Rubus idaeus L.). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, Volume 23, Issue 6, September 2010, Pages 540-544.

- Goto T, Teraminami A, Lee JY et al. Tiliroside, a glycosidic flavonoid, ameliorates obesity-induced metabolic disorders via activation of adiponectin signaling followed by enhancement of fatty acid oxidation in liver and skeletal muscle in obese—diabetic mice. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, Volume 23, Issue 7, July 2012, Pages 768-776.

- Haffner K, Rosenfeld HJ, Skrede G et al. Quality of red raspberry Rubus idaeus L. cultivars after storage in controlled and normal atmospheres. Postharvest Biology and Technology, Volume 24, Issue 3, April 2002, Pages 279-289.

- Jeong JB and Jeong HJ. Rheosmin, a naturally occurring phenolic compound inhibits LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 cells by blocking NF-kappa B activation pathway. Food and Chemical Toxicology, Volume 48, Issues 8—9, August—September 2010, Pages 2148-2153.

- Yang F, Basu TK, Ooraikul B. Studies on germination conditions and antioxidant contents of wheat grain. Department of Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Science, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2P5, Canada.

- Spina Cecarini V, Calzuola I, Marsili V, Angeletti M, Fioretti E, Tacconi R, Gianfranceschi GL, Eleuteri AM. Wheat sprout extract induces changes on 20S proteasomes functionality. University of Camerino, Department of Biology M.C.A., 62032 Camerino (MC), Italy.

- Indergaard, M. and Minsaas,J. 1991.2 Animal and human nutrition.” In Guiry, M>D. and Bunden, G. 1991. Seaweed Resources in Europe: Uses and Potential. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-92947-6.

- Butterfield (2000). “Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen.k n. sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes”. Paleobiology. 26(3): 386-404. Doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000) ISSN 0094-8373.

- Selective induction of apoptosis through activation of caspase-8 in human leukemia cells (Jurkat) by dandelion root extract, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20849941, Aug. 2012 , June 2012.

- The efficacy of dandelion root extract in inducing apoptosis in drug-resistant human melanoma cells, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21234313, Aug. 2012.

- Ingrid Kiefer , PhD, Peter Prock , MD, Catherine Lawrence , BEng, John Wise , PhD, Wilfried Bieger , MD, Peter Bayer. Supplementation with Mixed Fruit and Vegetable Juice Concentrates Increased Serum Antioxidants and Folate in Healthy AdultsJournal of the American College of Nutrition Volume 23, 2004 – Issue 3.

- Dietary Sulforaphane-Rich Broccoli Sprouts Reduce Colonization and Attenuate Gastritis in Helicobacter pylori–Infected Mice and Humans,” Cancer Prevention Research, April 2009, Volume 2, Issue 4

- Diet and Helicobacter pylori infection,” Prz Gastroenterol. 2016; 11(3): 150–154

- Dietary sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprouts reduce colonization and attenuate gastritis in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice and humans,” Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2009 Apr;2(4):353-60

- Dietary Amelioration of Helicobacter Infection,” Nutr Res. 2015 Jun; 35(6): 461–47

- Modulation of the metabolism of airborne pollutants by glucoraphanin-rich and sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprout beverages in Qidong, China,” Carcinogenesis (2012) 33 (1): 101-107

- Antioxidant enzyme induction: a new protective approach against the adverse effects of diesel exhaust particles,” Inhal Toxicol. 2007;19 Suppl 1:177-82

- Evaluation of protective effects of sulforaphane on DNA damage caused by exposure to low levels of pesticide mixture using comet assay,” J Environ Sci Health B. 2009 Sep;44(7):657-62

- Inhibition of mutagenicity of food-derived heterocyclic amines by sulforaphane–a constituent of broccoli,” Indian J Exp Biol. 2003 Mar;41(3):216-9.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA national nutrient database for standard reference, release 28. Web. 22 Feb. 2016.

- Stadlmayr, B., U.R. Charondiere, V.N. Enujiugha, et al. West African food composition table. Rome: The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2012.

- Goplan, C., B.V.R. Sastri, S.C. Balasubramanian, et al. Nutritive value of Indian foods. Hyderabad, India: National Institute of Nutrition; 1999.

- Sreelatha, S., and P. R. Padma. “Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of Moringa oleifera leaves in two stages of maturity.” Plant foods for human nutrition 64.4 (2009): 303-311.

- Razis, Ahmad Faizal Abdull, Muhammad Din Ibrahim, and Saie Brindha Kntayya. “Health benefits of Moringa oleifera.” Asian Pac J Cancer Prev15.20 (2014): 8571-8576.

- “This ‘Miracle Plant’ Balances Hormones & Improves Health in Many Ways.” Dr Axe. 2016. Web. 22 Feb. 2016.

- Kushwaha, Shalini, Paramjit Chawla, and Anita Kochhar. “Effect of supplementation of drumstick (Moringa oleifera) and amaranth (Amaranthus tricolor) leaves powder on antioxidant profile and oxidative status among postmenopausal women.” Journal of food science and technology 51.11 (2014): 3464-3469.

- Ghasi, S., E. Nwobodo, and J. O. Ofili. “Hypocholesterolemic effects of crude extract of leaf of Moringa oleifera Lam in high-fat diet fed Wistar rats.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 69.1 (2000): 21-25.

- Mehta, Komal, et al. “Effect of fruits of Moringa oleifera on the lipid profile of normal and hypercholesterolaemic rabbits.” Journal of ethnopharmacology 86.2 (2003): 191-195.

- Mbikay, Majambu. “Therapeutic potential of Moringa oleifera leaves in chronic hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia: a review” Frontiers in pharmacology 3 (2012).

- Sulaiman, Mohd Roslan, et al. “Evaluation of Moringa oleifera aqueous extract for antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities in animal models.” Pharmaceutical biology 46.12 (2008): 838-845.

- Mahajan, Shailaja G., and Anita A. Mehta. “Immunosuppressive activity of ethanolic extract of seeds of Moringa oleifera Lam. in experimental immune inflammation.” Journal of ethnopharmacology 130.1 (2010): 183-186.

- 1 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21486000, Inhibitory effect of acaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) pulp on IgE-mediated mast cell activation, Sept. 2012

- 2 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22961050, Inhibition of Mouse Urinary Bladder Carcinogenesis by Acai Fruit (Euterpe oleracea Martius) Intake, Sept. 2012

- 3 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21569436, Effects of Açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) berry preparation on metabolic parameters in a healthy overweight population: a pilot study, Sept. 2012

- Chen, Xu-bing, et al. “Potential AMPK activators of cucurbitane triterpenoids from Siraitia grosvenorii Swingle.” Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry 19.19 (2011): 5776-5781.

- Institute for Traditional Medicine. Sweet fruit used as a sugar substitute and medicinal herb. Available at www.itmonline.org/arts/luohanguo.htm.

- Swingle, WT. Momordica grosvenori Sp. Nov. the source of the Chinese Lo han kuo. Journal of the Arnold Arboretum. 1941;22:197-203.

- Kinghorn AD, Soejarto DD. Discovery of terpenoid and phenolic sweeteners from plants. Pure and Applied Chemistry. 2002;74:1169-1179. Available at pac.iupac.org/publications/pac/pdf/2002/pdf/7407×1169.pdf.

- Qi XY, Chen WJ, Zhang LQ, Xie BJ. Mogrosides extract from Siraitia grosvenori scavenges free radicals in vitro and lowers oxidative stress, serum glucose, and lipid levels in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Nutr Res. 2008;28:278-284.

- Suzuki YA, Tomoda M, Murata Y, et al. Antidiabetic effect of long-term supplementation with Siraitia grosvenori on the spontaneously diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rat. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:770-75.

- Hossen MA, Shinmei Y, Jiang S, et al. Effect of Lo Han Kuo (Siraitia grosvenori Swingle) on nasal rubbing and scratching behavior in ICR mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005; 28:238-241. Available at www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/bpb/28/2/28_2_238/_pdf.

- Ukiya M, Akihisa T, Tokuda H, et al. Inhibitory effects of cucurbitane glycosides and other triterpenoids from the fruit of Momordica grosvenori on epstein-barr virus early antigen induced by tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:6710-6715.

- Takasaki M, Konoshima T, Murata Y, et al. Anticarcinogenic activity of natural sweeteners, cucurbitane glycosides, from Momordica grosvenori. Cancer Lett. 2003;198:37-42

- Bittner et al, 2005. “Prescript-Assist probiotic-prebiotic treatment for irritable bowel syndrome: a methodologically oriented, 2-week, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical study.”,http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16117982.

- Bittner et al, 2007. “Prescript-assist probiotic-prebiotic treatment for irritable bowel syndrome: an open-label, partially controlled, 1-year extension of a previously published controlled clinical trial”,http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17692729.

- Tabbene et al, 2011. “Anti-candida effect of bacillomycin D-like lipopeptides from Bacillus subtilis B38”. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21204933.

- American College of Sports, M., A. American Dietetic, and C. Dietitians of, Joint Position Statement: nutrition and athletic performance. American College of Sports Medicine, American Dietetic Association, and Dietitians of Canada. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2000. 32(12): p. 2130-45.

- Marynowski, M., et al., Role of environmental pollution in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol, 2015. 21(40): p. 11371-8.

- Waterman, J.J. and R. Kapur, Upper gastrointestinal issues in athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep, 2012. 11(2): p. 99-104.

- Halvorsen, F.A., et al., Gastrointestinal disturbances in marathon runners. Br J Sports Med, 1990. 24(4): p. 266-8.

- Goodman, B.E., Insights into digestion and absorption of major nutrients in humans. Adv Physiol Educ, 2010. 34(2): p. 44-53.

- Levin, R.J., Digestion and absorption of carbohydrates–from molecules and membranes to humans. Am J Clin Nutr, 1994. 59(3 Suppl): p. 690S-698S.

- Tucci, S.A., E.J. Boyland, and J.C. Halford, The role of lipid and carbohydrate digestive enzyme inhibitors in the management of obesity: a review of current and emerging therapeutic agents. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes, 2010. 3: p. 125-43.

- Mukherjee, M., Human digestive and metabolic lipases – a brief review. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B-Enzymatic, 2003. 22(5-6): p. 369-376.

- Roxas, M., The role of enzyme supplementation in digestive disorders. Altern Med Rev, 2008. 13(4): p. 307-14.

- DeLuca HF, Cantorna MT. Vitamin D: its role and uses in immunology. FASEB Journal. 2001;15(14):2579– 85.

- DeLucia MC, Mitnick ME, Carpenter TO. Nutritional rickets with normal circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D: a call for reexamining the role of dietary calcium intake in North American infants. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88(8):3539–45.

- Diaz GD, Paraskeva C, Thomas MG, Binderup L, Hague A. Apoptosis is induced by the active metabolite of vitamin D3 and its analogue EB1089 in colorectal adenoma and carcinoma cells: possible implications for prevention and therapy. Cancer Research. 2000;60(8):2304–12.

- Diehl JW, Chiu MW. Effects of ambient sunlight and photoprotection on vitamin D status. Dermatologic Therapy. 2010;23(1):48–60.

- Diesing D, Cordes T, Fischer D, Diedrich K, Friedrich M. Vitamin D—metabolism in the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Anticancer Research. 2006;26(4A):2755–9.

- Glendenning P, Taranto M, Noble JM, Musk AA, Hammond C, Goldswain PR, Fraser WD, Vasikaran SD. Current assays overestimate 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and underestimate 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 compared with HPLC: need for assay-specific decision limits and metabolite-specific assays. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 2006;43(Pt 1):23–30.